Mutiny - Flow control and Back-pressure

Reactive Programming offers an elegant, flexible, and powerful way to write asynchronous code. It supports failure handling, both sequential and parallel operation composition, and plenty of operators. Reactive programming promotes data streams as a primary construct, and your code is observing streams and reacting to signals.

However, using data streams as primary constructs does not come without some issues. One of the main problems is the need for flow control.

The producer/consumer problem

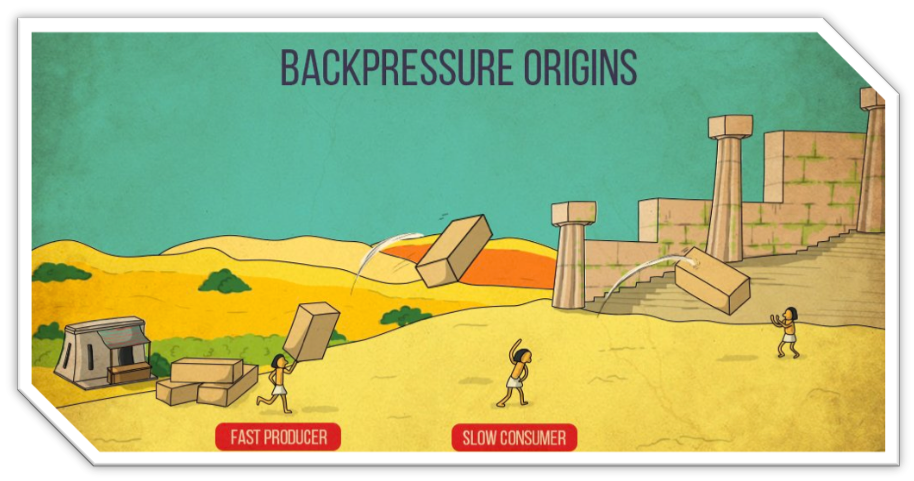

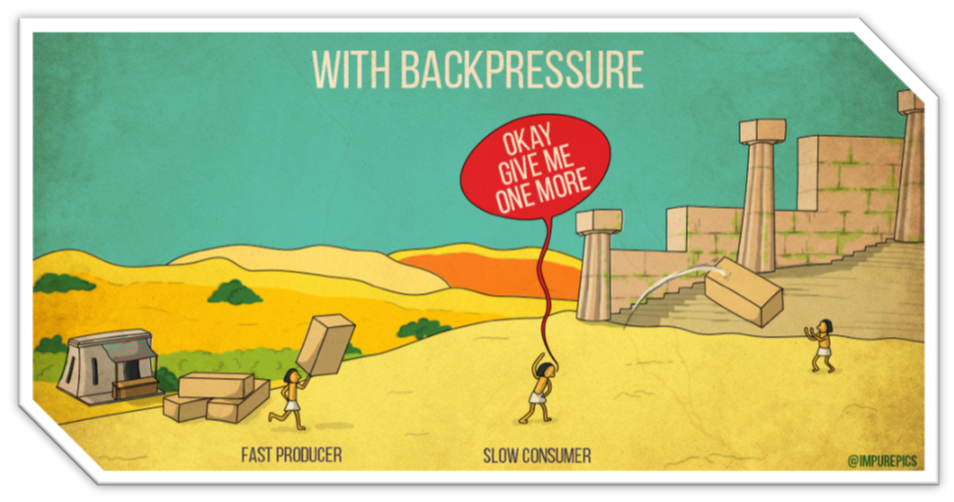

Let’s imagine a fast producer and a slow consumer. The producer sends events too quickly for the consumer that can’t keep up. That phenomenon is remarkably well illustrated in the following picture.

Let’s see some code. Imagine a producer emitting an event every ten milliseconds, while the consumer can only consume one per second.

Multi.createFrom().ticks().every(Duration.ofMillis(10))

.emitOn(Infrastructure.getDefaultExecutor())

.onItem().transform(BackPressureExample::canOnlyConsumeOneItemPerSecond)

.subscribe().with(

item -> System.out.println("Got item: " + item),

failure -> System.out.println("Got failure: " + failure)

);If you run that code, you will see that the subscriber gets a MissingBackPressureFailure, indicating that the downstream cannot keep up:

Got item: 0

Got failure: io.smallrye.mutiny.subscription.BackPressureFailure: Could not emit tick 16 due to lack of requests|

emitOn

In the previous code, you may wonder about the |

So, what can we do to handle this overflow?

Buffering items

The first natural solution uses buffers. The consumer can buffer the events, so it does not fail:

Using a buffer allows handling small bumps, but it’s not a long term solution. If we update the code to use a large buffer, the consumer can handle more events but eventually fails:

Multi.createFrom().ticks().every(Duration.ofMillis(10))

.onOverflow().buffer(250)

.emitOn(Infrastructure.getDefaultExecutor())

.onItem().transform(BufferingExample::canOnlyConsumeOneItemPerSecond)

.subscribe().with(

item -> System.out.println("Got item: " + item),

failure -> System.out.println("Got failure: " + failure)

);Got item: 0

Got item: 1

Got item: 2

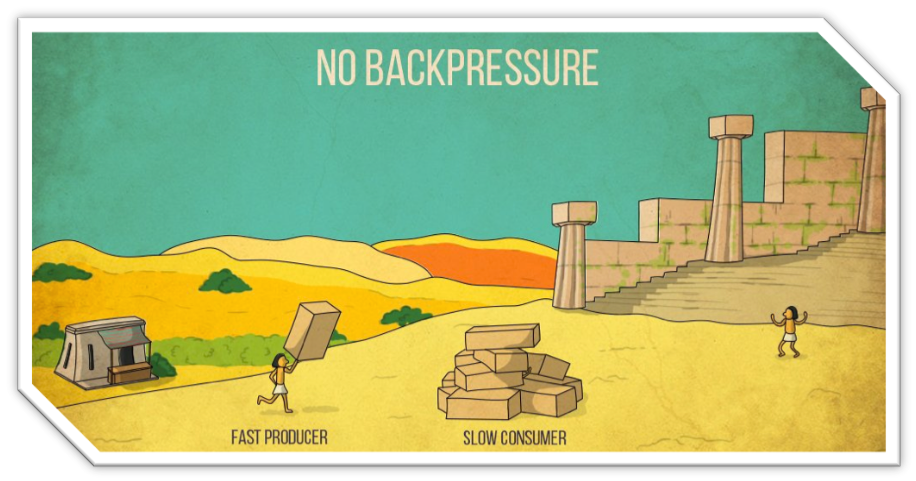

Got failure: io.smallrye.mutiny.subscription.BackPressureFailure: Buffer is full due to lack of downstream consumptionYou can imagine increasing the buffer’s size, but it’s hard to anticipate the optimal value. What about unbounded buffers? In general, that’s a terrible idea as you may run out of memory.

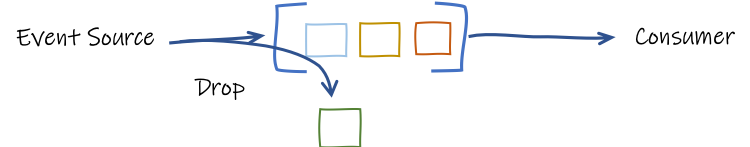

Dropping items

Another solution consists of dropping items:

You can drop the newest received items or oldest ones:

Multi.createFrom().ticks().every(Duration.ofMillis(10))

.onOverflow().drop(x -> System.out.println("Dropping item " + x))

.emitOn(Infrastructure.getDefaultExecutor())

.onItem().transform(DropExample::canOnlyConsumeOneItemPerSecond)

.transform().byTakingFirstItems(10)

.subscribe().with(

item -> System.out.println("Got item: " + item),

failure -> System.out.println("Got failure: " + failure)

);// ....

Dropping item 997

Dropping item 998

Dropping item 999

Dropping item 1000

Dropping item 1001

Dropping item 1002

Dropping item 1003

Got item: 9Dropping items provides a sustainable solution to our problem, but we are losing events! As we can see in the previous output, we may drop the high majority of items. In many cases, this is not acceptable.

So, we need another solution, a solution where the overall pace is adjusted to satisfy the pipeline’s slowest element. We need flow control.

What the heck is Back-Pressure?

You may have seen this term many times, and often associated with Reactive. In mechanics, back-pressure is a way to control the flow of fluid through pipes, leading to a pressure drop. That control can use reducers or bends. While very interesting, if you are a plumber, it’s not clear how it can help us here?

We can see our streams as a flow of fluid, and the set of stages (operator or subscriber) forms a pipe. We want to make the fluid flows as frictionless as possible without swirls and waves.

An interesting characteristic of fluid mechanics is how a downstream reduction of the throughput affects the upstream. Essentially, that’s what we need: a way for the downstream operators and subscribers to reduce the throughput, not only locally but also upstream.

Don’t be mistaken; back-pressure is not something new in the IT world and is not limited to Reactive. One of the most brilliant usages of back-pressure is in TCP. A reader, receiving data, can block the writer, on the other side of the wire, if it does not read the sent data. That way, the reader is never overwhelmed. But, the consequence need to be understood: blocking the writer may not be without side-effects.

There are other back-pressure implementations. AMQP uses a credit-based flow control, where you can only send if you have enough credit. Eclipse Vert.x back-pressure is based on pause/resume, where a consumer can pause the upstream until it catches up and resume it once back on track.

Introducing Reactive Streams

Let’s now focus on another back-pressure protocol: Reactive Streams.

It defines an asynchronous and back-pressure protocol suiting to our fast producer/slow consumer problem.

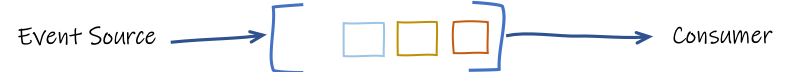

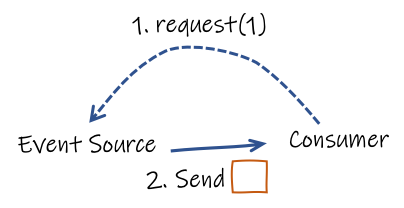

With Reactive Streams, the consumer, named Subscriber, requests items from the producer, named Publisher.

The Publisher cannot send more than the requested amount of items:

When the items are received and processed, the consumer can request more items, and so on. Thus, the consumer controls the flow.

Reactive Streams entities

To implement that protocol, Reactive Streams define a set of entities.

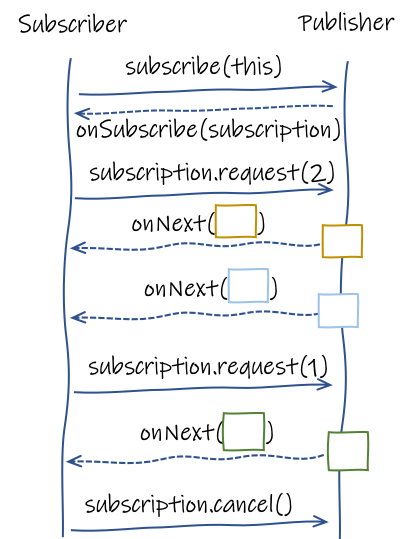

First, a Subscriber is a consumer.

It subscribes to a Publisher, producing items.

Then, the Publisher sends, asynchronously, a Subscription object to the Subscriber.

This Subscription is a contract.

With this Subscription, the Subscriber can request items and cancels the subscription when it does not want any more items.

Subscriber and a PublisherA Publisher cannot send more items than requested to the Subscriber, and the Subscriber can request more items at any time.

It is essential to understand that the requests and emissions are not necessarily happening synchronously.

A Subscriber can request three items, and the Publisher will send one by one when they are available.

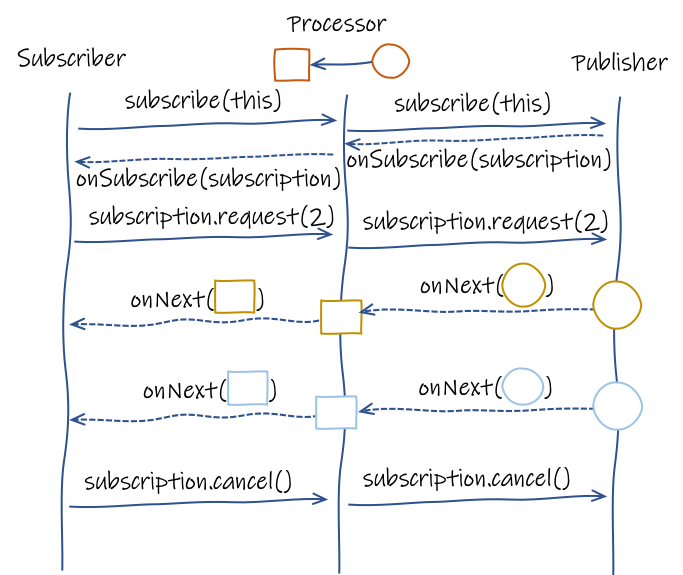

Reactive Streams introduces another entity named Processor.

A Processor is a Subscriber and a Publisher simultaneously.

In other words, it’s a link in our pipeline:

Subscriber, a Processor and a PublisherA Subscriber calls subscribe on a Processor.

Before receiving a Subscription, the Processor subscribes to its own upstream (the Publisher in the picture above).

When that upstream provides a Subscription to our Processor, it can give a Subscription to the Subscriber.

All these interactions are asynchronous.

When this handshake completes, the Subscriber can start requesting items.

The Processor is responsible for mediating the Subscriber requests with its upstream.

For example, as illustrated in the picture above, if the Subscriber requires two items, the Processor also requests two items to its own upstream.

Of course, depending on the Processor code, it may not be that simple.

What’s fundamental is that each Publisher and Processor enforces the flowing requests never to overload downstream Subscribers.

Be warned; it’s a trap!

If you look at the Reactive Streams API, you will find it straightforward. Be warned; it’s a trap! Behind this apparent simplicity, implementing Reactive Streams entities yourself is a nightmare. Reactive Streams come with a broad set of rules and a strict TCK.

But, no worries, Mutiny implements the Reactive Streams protocol for you.

In other words, when using Multi, you are using a Publisher following the Reactive Streams protocol.

All the subscription handshakes and requests negotiations are done for you.

Looking under the hood

I knew it! You are curious!

You can use onSubscribe().invoke() and onRequest().invoke() to check what’s going on:

Multi.createFrom().range(0, 10)

.onSubscribe().invoke(sub -> System.out.println("Received subscription: " + sub))

.onRequest().invoke(req -> System.out.println("Got a request: " + req))

.transform().byFilteringItemsWith(i -> i % 2 == 0)

.onItem().transform(i -> i * 100)

.subscribe().with(

i -> System.out.println("i: " + i)

);You can also go a step further and not only observing but also controlling the flow yourself:

Multi.createFrom().range(0, 10)

.onSubscribe().invoke(sub -> System.out.println("Received subscription: " + sub))

.onRequest().invoke(req -> System.out.println("Got a request: " + req))

.onItem().transform(i -> i * 100)

.subscribe().with(

subscription -> {

// Got the subscription

upstream.set(subscription);

subscription.request(1);

},

i -> {

System.out.println("i: " + i);

upstream.get().request(1);

},

f -> System.out.println("Failed with " + f),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);And, if you are a bit insane, you can even implement a Subscriber directly:

Multi.createFrom().range(0, 10)

.onSubscribe().invoke(sub -> System.out.println("Received subscription: " + sub))

.onRequest().invoke(req -> System.out.println("Got a request: " + req))

.onItem().transform(i -> i * 100)

.subscribe().withSubscriber(new Subscriber<Integer>() {

private Subscription subscription;

@Override

public void onSubscribe(Subscription s) {

this.subscription = s;

s.request(1);

}

@Override

public void onNext(Integer item) {

System.out.println("Got item " + item);

subscription.request(1);

}

@Override

public void onError(Throwable t) {

// ...

}

@Override

public void onComplete() {

// ...

}

}

);まとめ

This post described the different approaches offered by Mutiny to handle back-pressure.

The Reactive Streams protocol works well when you can control the pace of the upstream.

But it’s not always the case.

Streams representing physical entities are rarely controllable.

Imagine a stream emitting user’s keystrokes.

You cannot ask the users to slow down.

That would be a terrible user experience.

As we have seen above, time is also not something we can slow down, unfortunately…

In this case, the onOverflow() group lets you decide the mitigation, such as using buffers or dropping items.

It’s critical to avoid overwhelming downstream subscribers. It is the small crack that ripples in your system with dreadful consequences.